The Most Common Food Safety Incidents in the Last Decade in the U.S. (case study)

January 20, 2021

Abstract

More than 9 million foodborne illnesses are estimated to be caused by major pathogens acquired in the United States each year. CDC estimates that each year roughly 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) gets sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die of foodborne diseases. The 2018 World Bank report on the economic burden of foodborne diseases indicated that the total productivity loss associated with foodborne disease in low- and middle-income countries was estimated to cost US$ 95.2 billion per year. The aggregate economic costs for all foodborne illnesses in the United States in 2018 were estimated at $60 billion based on the basic cost-of-illness model. It should be noted that the basic cost-of-illness model includes economic estimates for medical costs, productivity losses, and illness-related mortality (based on hedonic value-of-statistical-life studies). These challenges put greater responsibility on food producers and handlers to ensure food safety. Small, local incidents can quickly evolve into a state-wide or national emergency due to product distribution speed and range. This approach is not feasible in our study to indicate which of the US states have more serious foodborne disease outbreaks with the exception of produce, which is grown in large volumes in both Salinas, California and Yuma, Arizona.

Figure 1 maps food flows at the Freight Analysis Framework (FAF) and county spatial scales. The links are depicted for all FAF flows and for the largest 5% of county estimates. These maps show aggregate food flows and the general spatial trends between the FAF and county spatial scales compare well. Figure 1 (A) depict total food flows(tons) for the FAF and Fig 1 (B) county scale. The density is much higher for the FAF data than inferred county results.

Figure 1: . Maps of food flow networks within the United States. Maps depict total food flows(tons) for the (A) FAF and (B) county scale. Links are shown for all FAF data and for the largest 5% of county links.

Avoiding these illnesses is challenging because resources are limited, and linking individuals’ health conditions to a particular food are rarely possible except during an outbreak’s epidemiological phase.

We attempted to develop a method of attributing illnesses to food commodities that use data from outbreaks associated with simple and complex foods. Using data from outbreak-associated illnesses for 2010–2020, we estimated annual US foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths attributable to each of 17 food commodities. The model attributed 4o% of illnesses to produce and found that more deaths were attributed to poultry than any other commodity. To the extent that these estimates reflect the commodities causing all foodborne illness, they indicate that efforts are particularly needed to prevent contamination of produce and poultry. Methods to incorporate data from other sources are required to improve attribution estimates for some commodities and agents.

Introduction

The inevitable process of globalization has created a dynamic market, which has radically intensified exchanges of goods and information and the flow of people among nations. Globalization provides consumers with more choices from a broad array of exotic foods. In addition to globalization, the complexity of food supply chains has intensified the difficulty to verify the safety and authenticity of foods exchanged across the globe.

While access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food is key to sustaining life and promoting good health, the recurring food safety incidents pose a significant risk to consumers’ health. Foodborne diseases may lead to acute poisoning or long-term diseases or long-lasting disability and death.

In view of recurrent food safety incidents, food supply in the 21st century should increase beyond food security and improving nutritional profile. The transparency of ingredients and regulations of foods play critical roles in the safety of food. The transparency includes regular monitoring, surveillance, and enforcement of food products for the sake of consumers’ general health and prevention of foodborne illnesses.

Henceforth, detecting the root causes of contamination or recall is critical in identifying the source of contamination in foodborne outbreaks and product recalls, thus helping food businesses develop risk mitigating strategies.

This study evaluates explicitly published food safety incidents and recalls collated from official websites such as the Center for Disease Control, FDA, WHO, FAO, and journal databases (e.g., Science Direct, PubMed, peer-reviewed papers). Due to the diversity of accumulation data, we concluded that there is no universal uniformity between countries for this research; therefore, we divided this research into three papers and included Europe and the rest of the countries in two additional articles.

The data collected from the references mentioned above provides concrete evidence that undeclared allergens and cross-contamination were identified as the top two recorded causes of food safety incidents and recalls. This study offers vital insights into US food safety incidents according to food and drinks categories, hazards and common contributory factors.

The following table represents the type and estimated percentage of food recalls aligned to a recognized food safety incidents category and based on reliable data sources.

| Type of Recall | Average percentage (2008-2018) |

| Allergens (including mislabelling) | 45% |

| Cross-contamination (biological hazards) | 40% |

| Chemical Hazards | 2.5% |

| Physical Hazards | 9.5% |

| Others | 3% |

Table 1: Global food safety incidents and/or recalls according to hazards from 2008 to 2018

The two common culprits of major food safety incidents and recalls are undeclared allergens and cross-contamination. However, this study’s focus was not only on recalls but also on identifying common contributory factors in food safety incidents resulting in product recalls, food poisoning incidents, and legal offences.

Cross-contamination of food and beverages can occur at all food processing steps. The processing steps that can cause food contamination include transportation from farm to processing facilities, processing steps in the manufacturing facilities due to lack of cleaning, insufficient personnel training, food packaging and storage. The possible contamination of food product during processing and packaging and storage lead to outbreaks. Therefore, identifying the causes of contamination is crucial to understand the potential sources and routes of contamination of foodborne outbreaks and product recalls. Understanding the root cause will result in developing steps to mitigate their occurrence.

In the US, the wrong label or use of the wrong packaging was identified as the most frequent problem resulting in food allergen recalls. This could be caused by ingredient mislabeled or an ingredient statement omission. An example is an ingredient used in the product that was not intended and not declared as an allergen, or the manufacturer was unaware of allergen labelling requirements for the target market. Furthermore, food fraud is a potential risk. For example, the Lockton Food and Beverage report (2017) highlighted that 32% of UK food and drinks manufacturers (n=200) could not guarantee the authenticity of the ingredients they source. More worryingly, 98% of respondents noted that retailers’ continued price pressure impacts the end product. Their coping strategies include reducing the product size or amount without changing the cost/price (also referred to as shrinkflation), sourcing cheaper and lower quality ingredients and cost-cutting in food safety and quality control.

The other types that resulted from the allergen recalls were also identified and categorized. One of the most common incidents reported was cross-contact, which usually occurs due to ineffective cleaning between products with different allergens. Lack of access to all parts of processing equipment for effective cleaning was also recorded as the reason for cross-contact. Another type of cross-contact happens due to process error. An unprocessed product (with an allergen) is added to another product without a known allergen.

While the root causes for the wrong label, omission, cross-contact, and errors by suppliers and unclear supply chain information are not fully identified, the lack of adequate training is a significant factor for most of these types of mistakes that result in a voluntary withdrawal or food safety recall incident. Milk was the most frequently undeclared allergen, and bakery products were the primary food products recalled.

There are many factors that have a negative impact on the safety of our food. This includes the lack of supply chain transparency on where and how the food was grown, harvested, processed and transported, technical incompetence due to a lack of education and training, ineffective implementation of food safety management systems and tools and ignorance of regulatory requirements. Food safety, nutrition and food security are linked in a complex manner, hence the saying “if it’s not safe, it’s not food” (unknown source). The unsafe food creates a vicious cycle of disease, illness and malnutrition, affecting the most vulnerable, including infants, young children, the elderly and the sick.

Foodborne illnesses associated with microbial pathogens or other food contaminants pose serious health threats in developing and developed countries. WHO estimates less than 10% of foodborne illness cases are reported. In contrast, less than 1% of cases are reported in developing nations. Foodborne diseases negatively impact socioeconomic development by putting pressure on health care systems and damaging national economies and trade.

Microbiological safety is critical in supplying safe food to consumers. It should be noted that food by nature is biological; hence, it can support the growth of microbials that are potential sources of foodborne diseases. My research shows that both viruses and bacteria are major sources of foodborne disease. The data in this research demonstrates that while viruses are more responsible for the majority of foodborne illnesses, most cases of hospitalizations and deaths associated with foodborne infections are due to bacterial agents. The illnesses range from mild gastroenteritis to neurologic, hepatic, and renal syndromes caused by either toxin from the disease-causing microbe. Foodborne bacterial agents are the leading cause of severe and fatal foodborne illnesses. As we see in the following pages, in the last decade of the 20th century, salmonella was the most frequent cause of bacterial foodborne illness, accounting for over 20000 cases. Norovirus was the most cause of viral foodborne illness, accounting for over 50,000 cases.

Inadequate recycling and waste disposal and lack of adequate cleaning of equipment and facilities lead to the accumulation of spoiled and contaminated food. This is called environmental hygiene. Poor sanitary conditions in the area where foods are processed and prepared contribute to poor food storage and transport as well as the selling of unhygienic food. This leads to an increased pest and insect population that can result in a risk of food contamination and spoilage.

Foodborne illnesses are usually infectious or toxic in nature and caused by bacteria, viruses, parasites or chemical substances entering the body through contaminated food or water. Foodborne pathogens can cause severe diarrhea or debilitating infections, including meningitis.

Chemical contamination can lead to acute poisoning or long-term diseases, such as cancer. Foodborne diseases may lead to long-lasting disability and death. Examples of unsafe food include uncooked foods of animal origin, fruits and vegetables contaminated with faeces, and raw shellfish containing marine biotoxins.

A wide range of microbiological, chemical and physical hazards can be found through the food supply chain to the point of consumption.

Potential microbiological hazards include the following:

Ø Salmonella and Campylobacter in raw meat and poultry Listeria monocytogenes in cooked, ready-to-eat (RTE) meats and soft cheeses

Ø E. coli O157:H7 in raw ground beef, raw milk and juices, and fresh produce

Ø Clostridium botulinum in soups and baked potatoes, and canned products

Ø Clostridium perfringens in dressed, roasted poultry and gravies Bacillus cereus in improperly cooled, cooked rice and potatoes

Ø Staphylococcus aureus in custard or creme-filled cakes

Potential chemical hazards include the following:

Ø Allergens

Ø Cleaning chemicals

Ø Pesticides and herbicides

Ø Mycotoxins

Ø Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

Ø Heavy metals

Potential physical hazards include the following:

Ø Broken glass and other foreign material

The burden of foodborne diseases

The difficulty in establishing causal relationships between food contamination and consequent illness or death has caused the burden of foodborne diseases to public health and economies has been underestimated.

It is not hard to understand that unsafe food poses global health threats, endangering everyone, including the most vulnerable groups such as Infants, young children, pregnant women, the elderly and those with an underlying illness.

The US has several surveillance programs under different authoritative administration. The FDA is the primary regulatory and enforcement agency that regulates about 80% of US food products. The USDA has its own surveillance program for foodborne illness outbreaks that fall under its jurisdiction and includes meat, poultry and eggs. Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) is an active surveillance system that links ten state and local health departments with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). FoodNet actively collects data from local physicians and clinical laboratories on the incidences of nine pathogens commonly transmitted through food in the 10 US states covering approximately 15% of the US population. The National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) also collects, analyses and summarizes data on infectious and non-infectious conditions, including foodborne outbreaks. Through NNDSS, CDC receives and uses these data to keep people healthy and defend America from health threats.

CDC publishes annual summaries of domestic foodborne disease outbreaks based on reports provided by local and territorial health departments. These summaries help public health practitioners better understand the germs, foods, settings, and contributing factors (for example, food not kept at the right temperature) involved in these outbreaks. They also can help identify emerging foodborne disease threats and can be used to shape and assess outbreak prevention measures.

Foods associated with food poisoning

While it remains challenging to identify food products that cause foodborne illness, we can categorize products that are more prone to cause food poisoning. Any food can get contaminated in the field, during processing, or during other stages in the food production chain, including through cross-contamination. According to the CDC, seven food categories are associated with food poisoning.

1. Raw foods of animal origin are the most likely to be contaminated, specifically raw or undercooked meat and poultry. The possible source of contamination is from Campylobacter, Salmonella, Clostridium Perfringens, E.coli, Yersinia.

2. Raw fruits and vegetables may cause food poisoning from harmful germs such as Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria. Fresh fruits and vegetables can be contaminated anywhere along the journey from farm to table, including cross-contamination in the kitchen.

3. Raw milk, soft cheeses, and other raw milk products, including ice cream and yogurt, carry harmful germs, including Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, E. coli, Listeria, and Salmonella.

4. Eggs can contain Salmonella that can make you sick, even if the egg looks clean and uncracked.

5. Seafood and raw shellfish such as oysters can contain Norovirus and Vibrio bacteria that can cause illness or death. In addition, seafood products were identified as the product category with the highest number of notifications, mainly due to the non-compliant presence of mercury, cadmium or both. It is known that seafood generally bioaccumulates heavy metal contaminants. Moreover, inadequate controls such as poor temperature control and lack of hygiene may result in contamination with pathogenic microorganisms, biotoxins and parasitic infestations.

6. The warm, humid conditions needed to grow sprouts are also ideal for germs to grow. Eating raw or lightly cooked sprouts, such as alfalfa, bean, or any other sprout, may lead to food poisoning from Salmonella, E. coli, or Listeria.

7. Flour is typically a raw agricultural product that hasn’t been treated to kill germs. Harmful germs can contaminate grain while it’s still in the field or at other steps as flour is produced.

While this is not explicitly included in single food categories associated with the most outbreak illnesses, ready-to-eat (RTE) meals recorded the second-highest number of incidents/ recalls. Some of the most common hazards contributing to the incidents were cross-contamination with Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, undeclared allergens and contamination with extraneous materials.

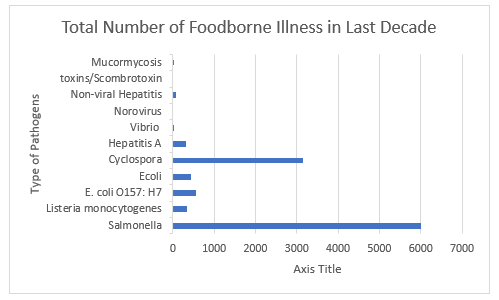

The top 5 food pathogens that result in most food safety incidents according to CDC, FDA in the US are Salmonella spp., listeria monocytogenes, norovirus, E. coli (all Shiga toxin-producing E. coli– (STEC), Enteropathogenic E. coli– (EPEC) Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) ), campylobacter. If we include clostridium perfringens in this list together, they accounted for roughly 9 out of 10 illnesses from outbreaks from 2011 to 2020. They appear to be included in most foodborne illnesses and outbreaks. Indeed there are some sporadic outbreaks with other pathogens such as Shigella and Cyclospora. For instance, there were some outbreaks related to Cyclospora. Cyclospora is a coccidian parasite that causes diarrheal disease in humans called cyclosporiasis. A troublesome Cyclospora outbreak continues to grow in North America, with 206 cases in the mid-west United States. Most of the outbreaks of Cyclospora infections traced to Fresh Express bagged garden salad products containing lettuce, carrots, and red cabbage. The food safety incidents with Shigella and Cyclospora are on the rise. In our view, we should expect to see more food safety incidents and recalls with these two pathogens if the preventive measures are not established.

Salmonella spp. is often found in livestock, wild animals, birds, pets, animal manure and contaminated irrigation water, which cause the contamination of fresh produce at the pre-harvest stage. Salmonella can withstand extreme environmental conditions. This includes survival for long periods of time under low AW conditions desiccation. Therefore the pathogen can survive in low water activity foods such as chocolate and peanut butter. Salmonella Enteritidis is the most common strain of salmonella in our food supply. SalmonellaTyphimurium is the second most common serotype associated with foodborne illness. SalmonellaNewport is currently the third most common Salmonella serotype associated with foodborne illnesses. Broadly, Salmonella affects foods such as raw meat, poultry seafood, raw eggs, and fruits and vegetables.

Salmonella spp. is associated with the highest number of reported bacterial foodborne outbreaks and was among the top-5 food-pathogen combinations in terms of the overall number of cases of illness and hospitalizations in outbreaks. It appears from the data that Salmonella remains the number one reason for bacterial-related foodborne incidents in last decade. For instance, there was an outbreak of Salmonella Enteritidis in the United States linked to the consumption of fresh peaches produced in the U.S. More than 100 people infected with the outbreak strain were reported from 17 states in the U.S., and outbreak was extended to Canada, and many other countries that product was exported.

Listeria monocytogenes is one of the leading causes of death from food-borne pathogens especially in pregnant women, newborns, the elderly, and immuno-compromised individuals. Listeria monocytogenes remains a major challenge for ready-to-eat food, cooked meat and fish products, and dairy processors. L. monocytogenes is environmentally ubiquitous and can survive and grow in hostile conditions such as refrigeration temperature, low pH and high salt concentration. There are several RTE foods such as delicatessen meats, poultry products, seafood and dairy products are high-risk vehicles for L. monocytogenes as these foods tend to be chilled and provide a suitable environment for L. monocytogenes to grow. Listeriosis outbreaks were linked to seafood, dairy, meat and vegetable products. However, listeriosis outbreaks were recently associated with unconventional food vehicles such as fresh produce (e.g. celery, cantaloupe, mung bean sprouts, stone fruits, caramel apples) and ice cream and vegetable products.

Norovirus is associated with the highest number of reported viral foodborne outbreaks and was among the top-5 food-pathogen combinations in terms of the overall number of cases of illness and hospitalizations in outbreaks. It cause the majority of acute viral gastroenteritis cases worldwide. Fecal-oral spread is the primary mode of transmission. The virus’s abilities to withstand a wide range of temperatures (from freezing to 60 °C) and to persist on environmental surfaces and food items contribute to rapid dissemination, particularly via secondary spread (via food handlers or to family members). Food can be contaminated at the source (via contaminated water) or during preparation. Norovirus outbreaks occur frequently in US and rest of the world. Foods that are commonly involved in norovirus outbreaks include are leafy greens, fresh fruits (such as raspberries) and frozen berries, and shellfish.

Escherichia coli comprise a large and diverse group of bacteria. Transmission of E. coli occurs when food or water that is contaminated with feces of infected humans or animals is consumed. Contamination of animal products often occurs during the slaughter and processing of animals. The use of manure from cattle or other animals as fertilizer for agricultural crops can contaminate produce and irrigation water. E. coli can survive for long periods in the environment and can proliferate in vegetables and other foods. Pathogenic E. coli have been categorized into six groups according to the pathogenic mechanisms. The two most caused outbreaks are (1) Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC); (2) Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC, also known as Shiga toxin—producing E. coli [STEC]. STEC strain O157:H7 emerged as a significant public health threat in last two decades. Because its presence in guts of ruminants in particular cow and sheep undercooked ground meat has been one of the main reasons for food safety incidents and food recalls. A wide variety of foods, including fresh produce (such as romaine lettuce), have since served as a vehicle for E. coli O157:H7 outbreaks.

Campylobacters have been found in wild birds, poultry, pigs, cattle, domesticated animals, unpasteurized milk, produce, and contaminated water. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) lists Campylobacter as the fifth most costly foodborne pathogen, accounting for ~$2 billion, ~8,000 hospitalizations, and ~70 deaths annually. They are transmitted to humans by a fecal-to-oral route and the ingestion of contaminated water and ice. Most cases of Campylobacter infections are associated with eating raw or undercooked poultry. Campylobacter jejuni is one of the most common causes of diarrheal illness and responsible for approximately most food safety illnesses related to Campylobacter. Campylobacter grow optimally at 37–42 °C, however cannot tolerate drying and are unable to grow in atmospheric levels of oxygen .

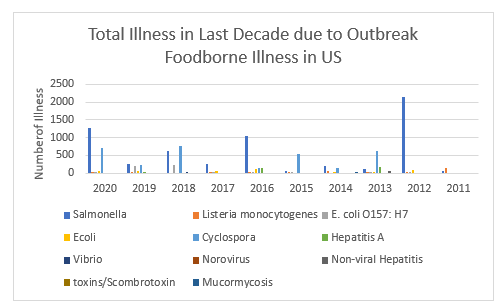

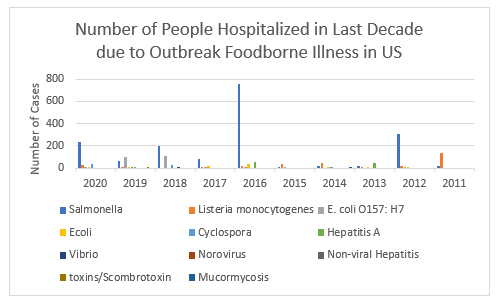

The foodborne outbreak in last decade is investigated. Fortunately FDA and CDC recorded all data and we could extract each type of outbreak in the last ten years in United States. There are complete uniformity in data between CDC and FDA. The following is a list of outbreak investigations being managed by FDA’s CORE Response Teams. The investigations are in a variety of stages, meaning that some outbreaks have limited information, and others may be near completion.

Fig 2: Total Illness in Last Decade due to Outbreak Foodborne Illness in US

Fig 3:Number of people hospitalized in last decade due to outbreak foodborne illness in US

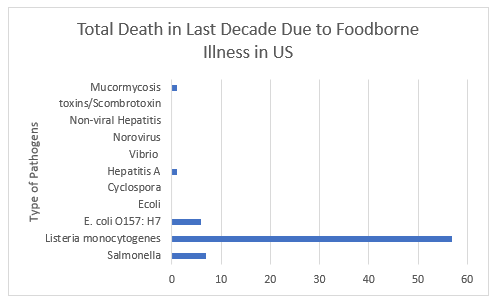

Fig 4: Number of people died in last decade due to outbreak foodborne illness in US

Fig 5: Total number of foodborne illness in last decade in US

Fig 6:Totalnumber of people hospitalized in last decade due to outbreak foodborne illness in US

Fig 7:Total Death in last Decade due to foodborne illness in US

When two or more people become ill from eating the same contaminated food or drink, the event is called a foodborne disease outbreak.

Outbreaks are caused by pathogens, which include germs (bacteria, viruses, and parasites), chemicals, and toxins. Although most foodborne illnesses are not part of a recognized outbreak, outbreaks provide important insights into how pathogens are spread, which food and pathogen combinations make people sick, and how to prevent foodborne illnesses.

CDC publishes annual summaries of domestic foodborne disease outbreaks based on reports provided by state, local, and territorial health departments. These summaries help public health practitioners better understand the germs, foods, settings, and contributing factors (for example, food not kept at the right temperature) involved in these outbreaks. They also can help identify emerging foodborne disease threats and can be used to shape and assess outbreak prevention measures. CDC summarizes foodborne disease outbreak data in an annual surveillance report and makes the data available to the public through the NORS Dashboard. Table 2 provides the number of the outbreals, recalls illnesses, hospitalizations and death from 2011 to 2017.

| Cases | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| No. Outbreaks | 801 | 831 | 818 | 864 | 902 | 839 | 841 |

| No. Illness | 14,140 | 14,972 | 13,360 | 13,246 | 15,202 | 14,259 | 14,481 |

| No. Hospitalizations | 956 | 794 | 1,062 | 712 | 950 | 875 | 827 |

| No. Deaths | 45 | 23 | 16 | 21 | 15 | 17 | 20 |

| No. Food Recalls | 27 | 20 | 14 | 21 | 20 | 18 | 14 |

Table 2: Annual summaries of domestic foodborne disease outbreaks published by CDC

After reviweing the highest number cases in each year. It was noticed that there are two pathogens appear in each year with highest cases of illnesses. Table shows the highest number of illness for these two most apparent pathogen that cause highest number of illnesses.

| Cases | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Norovirus | 5135 | 6009 | 4,999 | 5,340 | 5,454 | 5,934 | 6,340 |

| Salmonella | 3047 | 3394 | 3,593 | 2,563 | 4,035 | 3,081 | 3,061 |

Table 3 : The two pathogens that caused higher number of illnesses in the seven years

The food commodity with highest cases of illness without any priority are turkey, chicken, pork, mollusks, leafy vegetables,fruits, fish, dairy and grains and beans. In prticular, poultry and produce are the two food commodities with highest number of illnesses and deaths. There are two particular incidents in 2015 and 2014. Thefood categories associated with the most outbreak illnesses were seeded vegetables, such as cucumbers or tomatoes with 1,121 illnesses in 2015 and 428 illnesses in 2014.

The highest number of death in overall both in CDC annual report and FDA yearly report was related to Listeria Monocytogenes and Salmonella. The highest number of deaths was related to listeria monocytogenes in fruits with 35 people in 2011. Whole cantaloupe from a single farm was associated with a large, multistate outbreak in 2011. This event caused the most deaths from an outbreak of foodborne illness in the USA in more than 80 years.

In the past, foods most commonly identified as vehicles of L. monocytogenes transmission included unpasteurized milk and dairy products, soft cheese varieties, cooked ready-to-eat sausages and sliced meats (often referred to as ‘deli meats’), refrigerated smoked seafood, and refrigerated pâtés or meat spreads. Over the last decade, several novel food vehicles have been implicated in listeriosis outbreaks and recalls, such as raw sprouts and the previously mentioned whole cantaloupe melons.

Over the last decade, an increasing number of events have been associated with foods not traditionally recognized as vehicles for Listeria transmission, and a rise not only in US but in international events was noted. Informing high-risk individuals such as pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals of safe food handling practices is warranted. To ensure timely recall of contaminated food products, open data sharing and communication across borders is critical. Changes in food production and distribution, and improved diagnostics may have contributed to the observed changes.

Pathogenic E. coli is a major cause of outbreaks and is often associated with consumption of raw or undercooked, contaminated beef. It is interesting to note that there were very few Campylobacter incidents (with known/suspected causes) reported in most of the databases. Campylobacteriosis remains one of the leading cause of foodborne illness in the US according to CDC in 2018. Previous source attribution studies identified chicken and poultry meat as major risk factors for Campylobacter infections.

While it is not feasible to have precise percentage of the pathogens that cause foodborne illness in each year it is possible to have rough estimate of pathogens that caused highest number of food safety illness.

Estimations of Foodborne Illness based on best available data

| Pathogens | First Decade of 2020 | Second Decade of 2020 |

| Norovirus | 56% | 48% |

| Salmonella spp. | 11% | 27% |

| Clostridium Perfringens | 10% | 8% |

| Campylobacter spp. | 9% | 6% |

| E.coli STEC | 5% | 3% |

| L. Monocytogenes | 1% | 1% |

Table 4: Estimations of Hospitalization from Foodborne Illness based on best available data

| Pathogens | Second Decade of 2020 |

| Norovirus | ~2% |

| Salmonella spp. | ~15% |

| Clostridium Perfringens | ~1% |

| Campylobacter spp. | ~10% |

| E. coli STEC | ~27% |

| L. Monocytogenes | ~90% |

Table 5: Estimations of Hospitalization from Foodborne Illness based on best available data. The average is based on the number of people become ill and later hospitalized because of the severity of illness. For instance for 10 person become ill with L. monocytogenes 9 people approximately hospitalized.

In estimation and calculations data from CDC Annual review based on Surveillance for Foodborne Disease Outbreaks United States is used. The average is calculated based on number of those who accepted to hospital (based on detection on particular pathogen divided to number of total illness (CE = confirmed etiology; SE = suspected etiology). There are several other assumptions that must be stated. First, data used for second decade is based on 8 available years published data from CDC, FDA, USDA, Food Net, CDC Surveillance report. Therefore, the result cannot be extrapolated to cover the whole decade. Second, in calculation, both confirmed and suspected etiology are used. This could have impact on making conclusions on number of illness, hospitalization. Third, from 31 known pathogens studied in all aforementioned references only 6 pathogens which caused highest foodborne outbreaks were selected. Therefore, the rest of pathogens and their impacts on the safety of food should not be dismissed.

With all of these assumptions and uncertainties done in this study, one can still conclude that non-typhodial Salmonella and Norovirus are the two pathogens behind most of the outbreaks. In fact the typhoidal Salmonella spp. has been reduced significantly compare to the first decade of 2020.The three pathogens that caused highest number of hospitalizations due to foodborne illness are nontyphoidal Salmonella spp., Norovirus, E.coli STEC. The interesting fact is while the number of hospitalization due to L. Monocytogenes is lower than the stated three pathogens, the average percentage of those who are accepted as confirmed etiology by Listeria to hospital is 90%. In other words from 10 persons who become ill with the L. Monocytogenes 9 persons will end up to hospital.

While there are only an estimated 1500 cases of Listeria monocytogenes per year in the US, because of the high fatality rate, we have always recognized the impact in ‘human terms’. It still results in the biggest impact on quality and quantity of life, and almost all of this burden falls on the individuals who suffer from it and grief of those close to them. Over the last 10 to 15 years, increasing evidence suggests that persistence of L. monocytogenes in food processing plants for years or even decades is an important factor in the transmission of this foodborne pathogen and the root cause of a number of human listeriosis outbreaks. L. monocytogenes persistence in other food-associated environments (e.g., farms and retail establishments) may also contribute to food contamination and transmission of the pathogen to humans.

In contrast, foodborne norovirus causes an estimated 5 million episodes of foodborne illnesses in the US annually and Salmonella causes an estimated 1 million of foodborne illness. These two have a far larger economic impact. There is a significant burden caused by those who suffer from the illness. As a result, we believe the overall burden to the US caused by foodborne Norovirus and Salmonella are far more greater than Listeria monocytogenes, and are the biggest known cause of economic and human suffering attributed to a foodborne illness.

The leading causes of death if we include data from both FDA, USDA are nontyphoidal Salmonella spp, Listeria monocytogenes and Norovirus.

Limitations in This Case Study

The findings in this report have at least four limitations. First, only a small proportion of foodborne illnesses that occur each year are identified as being associated with outbreaks. The extent to which the distribution of food vehicles and locations of preparation implicated in outbreaks reflect the same vehicles and locations as sporadic foodborne illnesses is unknown. Second, many outbreaks had an unknown etiology, an unknown food vehicle, or both, and conclusions drawn from outbreaks with a confirmed etiology or food vehicle might not apply to other outbreaks. Third, CDC’s outbreak surveillance system is dynamic. Agencies can submit new reports and change or delete reports as new information becomes available. Therefore, the results of this analysis might differ from those in other reports. One of the references is Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet). The FoodNet conducts surveillance for Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157 and non-O157, Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia infections diagnosed by laboratory testing of samples from patients. It is a collaborative program among CDC and 10 state health departments, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS)External, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) The surveillance area includes 15% of the United States population (48 million persons). FoodNet is the principal foodborne disease component of CDC’s Emerging Infections Program. There are two issues. First it does not cover the whole population in US and second it only covers 8 pathogens and dismiss critical pathogen such as Norovirus; therefore analysis of data cannot be conclusive. Fourth, part of the observed increase in incidence is likely due to increased use of culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs) that identify previously unrecognized infections. Changes in clinicians’ ordering practices and varying test sensitivities and specificities might also contribute to this observation. Finally, year-to-year changes in incidence might not reflect sustained trends. The landscape of foodborne disease continues to change, as do the methods to determine the incidence and sources of these infections.

Conclusion:

Food safety incidents involve all four hazard categories (biological,

chemical, physical, allergen) but majority are in allergens and microbiological categories. Cross contamination (microbiological) and undeclared allergens were the most frequently cited causes of specific

incidents, making up 69% of the total. Microbiological outbreaks are often investigated in detail to determine the implicated food and sources of contamination e.g. raw materials and/or processing environment. Similarly, it is difficult to identify the root cause of the problem i.e. how did the contaminated raw material contaminate the processing environment or how did the pre-harvest conditions contaminate the food products. Therefore, it is important to examine a range of incidents in depth from a qualitative perspective in order to try to close this data gap that is essential to identify the root causes of the food safety incidents.

Trend analysis of product notifications and root cause analysis will benefit food regulators and industry by providing guidance on areas of focus for the prevention of incidents. We noticed in our study there has been an increase in foodborne disease outbreaks associated with consumption of raw and/or minimally processed fruits and vegetables. The recent outbreaks include E. coli O157:H7 in leafy greens including romaine lettuce, alfalfa sprouts, in mixed salad leaves and Salmonella on rock melons are proof of this observation. The sources and established contamination routes of pathogens include agricultural inputs such as contaminated irrigation water, inadequately composted manure, contaminated water used in reconstituted pesticides, soil, livestock, wild animals (including insects)and the ability of microorganisms to colonize and persist in fresh produce.

Laboratory-diagnosed non-O157 STEC infections continue to increase. Although STEC O157 infections appear to be decreasing, outbreaks linked to leafy greens continue. While Produce is an important part of our healthy diet it is also an important source for Cyclospora, Listeria, and Salmonella.

Future Scope

This case only reveals a minuscule picture of food safety issue in US. Nonetheless, it appears that we continuously see a resurrect of a common pathogen in a typical food product. A key part of tackling foodborne illnesses, like many public health issues, is that we need to make the right choices. There are so many choices often relate to what we prioritize and target when we develop new guidance or carry out risk assessments. It is either the risk assessment is setup wrongly or the policy developed is not followed rigorously.

Consequently, we now understand that almost 80 percent of the total burden caused by foodborne illnesses can be attributed to suffering and related fatalities. The data speak for itself. We also have an entirely better understanding of how different illnesses compare to each other, not just from the number of cases there are, however the suffering that each case is likely to cause. When it comes to protecting the public, this kind of information is vital. In my view, when we review each food safety incident, which results to illness we need to take into account its severity and whether they have longer term health implications. In fact, from risk management point of view, this provides a more comparable way of comparison for the impact of different illnesses. Because this demonstrates the risk of disease to public health from both economic impacts (like medical costs, individual expenses, lost earnings and school absence), as well as the non-economic ones (such as pain, suffering or grief).

The topic is already well known. The incidence of most infections transmitted commonly through food has not declined for many years. It is obvious we see some improvement and some disappointments. The detection method has drastically improved. This case study only used the real data and these records shows that incidence of infections caused by Listeria, Salmonella, Norovirus, Campylobacter remained unchanged, and those caused by all other pathogens such as non-pathogenic E.coli, Cyclospora, Shigella increased in last few years of decade. Infections caused by Salmonella serotype Enteritidis, did not decline; however, serotype Typhimurium infections continued to decline. What are the implications for public health practice? New strategies that target particular serotypes and more widespread implementation of known prevention measures are needed to reduce Salmonella illnesses. Reductions in Salmonella serotype Typhimurium suggest that targeted interventions (e.g., vaccinating chickens and other food animals) might decrease human infections. Isolates are needed to subtype bacteria so that sources of illnesses can be determined.

References:

Determining common contributory factors in food safety incidents – A review of global outbreaks and recalls 2008–2018 Jan Mei Soon∗, Anna K.M. Brazier, Carol A. Wallace

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/17/1/p1-1101_article

https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/public-health-advisories-investigations-foodborne-illness-outbreaks

Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet)- https://www.cdc.gov/foodnet/sites.html

Foodborne pathogens AIMS Microbiology, 3(3): 529-563. DOI: 10.3934/microbiol.2017.3.529

Characteristics of Campylobacter, Salmonella Infections and Acute Gastroenteritis in Older Adults in Australia, Canada, and the United States HHS Public Access: Clin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2020 October 15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6606397/pdf/nihms-1028492.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture-Food Safety and Inspection

https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/data-collection-and-reports/fsis-data-analysis-and-reporting/fsis-data/data-collectionervice

WHO Estimates of the Global Burden of Foodborne Diseases-Burden Epidemiology Reference Group 2007-2015

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/199350/9789241565165_eng.pdf?sequence=1

Recalls, Market Withdrawals, & Safety Alerts

https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts

Environmental Research: Food flows between counties in the United States Xiaowen Lin et al 2019 Environ. Res. Lett. 14 084011

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab29ae/pdf

Attribution of Foodborne Illnesses, Hospitalizations, and Deaths to Food Commodities by using Outbreak Data, United States, 1998–2008

Emerging Infectious Diseases Volume 19, Number 3—March 2013

Robert M. Hoekstra, Tracy Ayers, Robert V. Tauxe, Christopher R. Braden, Frederick J. Angulo, and Patricia M. Griffin

Author affiliations: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Food Crises and Food Safety Incidents in European Union, United States, and Maghreb Area: Current Risk Communication Strategies and New Approaches

March 2018Journal of AOAC International 101(4)

DOI: 10.5740/jaoacint.17-0446

Food safety in the 21st century

ScienceDirect: Biomedical Journal 41 ( 2018) 88-95

Fred Fung, Huei-Shyong Wang, Suresh Menon

The Economic Burden of Foodborne Illness in the United States Food Safety Economics pp 123-142 Robert L. Scharff

Economic Burden from Health Losses Due to Foodborne Illness in the United States January 2012Journal of Food Protection 75(1):123-31 Robert L. Scharff

MMWR Reports on Foodborne Illness and Outbreaks https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/multistate-outbreaks/reports.html

Salmonella infection

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/salmonella/symptoms-causes/syc-2035532

- bmarandi

Expert in International Standards and compliance for your Food and Beverage Products. We help Companies Reach Global Markets and Increase Sales. We Guarantee your success. Our Compliance Services Have Supported Companies Like Boundless Impact, Eat Good Fish, Shrew Food, Orochem Technologies Inc., Decernis LLC, , Dianapetfood S.A.S.

With 20 years experience in the food industry we serve our clients on compliance issues with regard to the food safety, food products, food additives, food-contact substances and dietary supplements regulations. We have extensive background in implementing standards and food products' regulations.

- The Most Common Food Safety Incidents in the Last Decade in the U.S. (case study) January 20, 2021

- The future of alternative proteins and in its impact on food industry December 7, 2020

- Foreign Supplier Verification Program November 8, 2020

- The Precautionary Principle in Food Regulation November 8, 2020

- The Effective Virus Control in Food Production and Food Processing Facilities October 27, 2020