A PATH TO FOOD WASTE REDUCTION

Executive Summary

An estimated one-third of all food grown and processed worldwide is classified as either food loss in the pre-consumption stages or food waste in food service and homes. In an age when an estimated one billion people go hungry, this is wasteful, costly, and an intolerable situation. Food loss and food waste (FLW) represent a wastage of labour, water, energy, land and other natural resources that were consumed in growing, harvesting, processing, distribution and storage of our food.

Food embodies much more than what is present on our plates. It is, therefore, important that we recognize, appreciate and respect the value of food. We all have a part to play in FLW reduction, not only for the sake of the food but for the resources that go into our food.[1] This white paper describes practical options to address and reduce FLW. As such, the focus of this paper is on the clear definition of date code marking and the reasons why clear definition will contribute to FLW reduction.

Keywords: Food waste, food loss, date code marking, FLW

The main sources of FLW. There are two sources of FLW, and that is, food loss and food waste. We need to have clear definition of both terms.

General definition of Food Loss: it typically takes place at the production, storage, processing, and distribution stages in the food value chain. This is often call the ‘pre-consumption’ stages of the food chain.

FAO definition of Food Loss: “Food Loss” refers to any food that is lost in the supply chain between the producer and the market. This may be the result of pre-harvest problems, such as pest infestations, or problems in harvesting, handling, storage, packing or transportation”. Some of the underlying causes of food loss include the inadequacy of infrastructure, markets, price mechanisms or even the lack of legal frameworks. Avocados crushed during transport because of improper packaging is one example of food loss.1

Typical Causes of Food Loss

Absence of integrity in supply chain normally results in food loss. There are some consistency in failure in food production systems that leads to food loss. Some of the main reasons as follows:[2]

1. Agriculture and farming production

2. Storage and transportation

3. Environmental impacts

4. Processing

5. Poor or inadequate Marketing

General definition of Food Waste: it ” refers to food that is of good quality and fit for consumption, but does not get consumed because it is discarded―either before or after it is left to spoil.[3]

FAO definition of Food Waste: “Food Waste”, on the other hand, refers to the discarding or alternative (non-food) use of food that is safe and nutritious for human consumption.[4] Food is wasted in many ways:

Typical Causes of Food Waste

Retailers have appearance quality standards which is different from national quality standards.[5]

Causes of Food Loss and food waste in Developing Countries

There are some fundamental differences between causes of food loss and waste between developing and developed countries. In brief if we want to identify some of the major reasons of food loss in developing countries, we can list some of them as below;

Causes of Food Loss and food waste in Developed Countries

While the major reasons for food loss in developing countries are originated from lack of effective market systems and lack of modern technology, the causes of food loss in developed countries are derived from following matters.2,[7]

Practical Solution to Food Loss and Food Waste

One third of all food produced globally is either lost or wasted. There are some practical solutions that need to be implemented for its effectiveness at national and global stage. However, the solutions could be a bit different from developed countries to developing countries.[8]

Practical Solution Proposed by some Countries

Composting

One proposed solution to food waste is to compost. This is indeed the most common ways to reduce the food waste that has already been disposed or ready to be disposed.

Rather than discarding scraps, one can compost certain foods and turn it into nutrient-rich fertilizer.

Composting is defined as the natural process of decomposition and recycling of organic materials into a partially decomposed rich soil amendment known as compost. For any food business or operation producing food waste, this organic material can be easily decomposed into high quality compost.[9]

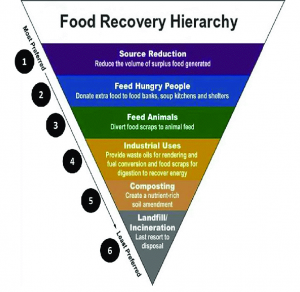

One should bear in mind that composting should not encourage the food businesses in producing more waste. Moreover, the EPA has a Food Recovery Hierarchy diagram [10] (see figure 1) on how we use our food, stating first that we should reduce the waste we create, then donate food, try to feed livestock, use waste for industrial energy and then compost.[11]

The Food Recovery Hierarchy

The Hierarchy suggests actions in the subsequent order by – prevention, donation, composting and/or anaerobic digestion. The top levels of the hierarchy are the best ways to prevent and divert wasted food because they create the most benefits for the environment, society and the economy. In summary, while composting is really valuable it should not be anyone’s priority.

Figure 1: The Food Recovery Hierarchy courtesy to EPA[12]

It should be noted that the composition and nutritional value of food waste is critical to ascertain where value-adding can be applied. Access to information on the volume, type and nutritional composition of food waste assists in supporting investment decisions on product development.[13] For example, food waste that can be used for animal consumption may have different characteristics to the type used for composting or energy generation.[14]

Anaerobic Digestion

The biochemical and chemical characteristics of food waste make it very attractive as a digestion substrate as it has a high methane potential and is readily degradable. Anaerobic digestion is a process that allows energy to be generated from organic waste. The process for converting of biodegradable material to source of energy as follows.

Donate to food banks and farms

This is one of the initiatives started with FAO. Food banks play a vital role in redirecting surplus, wholesome food to the hungry. In light of the international community’s commitment to end hunger by 2030, as articulated in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[16],[17]

FAO defined food bank’s role to reduce food waste with two practical options.

First, is to recover safe and nutritious food (processed, semi-processed or raw) which is fit for human consumption which would otherwise be disposed or wasted from any part of supply chains of the food system. Second, is to redistribute safe and nutritious food which is in accordance to appropriate safety, quality and regulatory frameworks directly or through intermediaries, to those having access to it for food intake. (FAO, 2015).[18]

Many countries around the globe have started addressing the both area of recovery and redistribution of safe and nutritious food fit for human consumption through, developing guidance on the implementation of such actions. For complete list of actions for each country visit Country level guidance – selected information at stated footnote.[19]

Initiatives across the globe

The extent of food wasted resource has prompted a number of initiatives across the globe to address food waste.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations Save Food Initiative helps countries in Asia, the Pacific, Middle East and others identify and develop food waste reduction strategies adjusted to the specific needs of regions, sub-regions and countries.[20]

Canada

Canada is one of the countries with major food waste. For the average Canadian household that amounts to 140 kilograms of wasted food per year. There are some practical solutions introduced by health authorities in Canada. Here are some ways introduced by Health Canada that can help to increase the sustainability of food system:

Reduce: Be sure to plan your meals before you shop so that you only buy what you can consume before it spoils and ends up in the garbage

Recover: Donate to food programs that help people in your community

Recycle: Participate in organic waste collection programs or start a composter in your backyard and use the Greenhouse Gas Calculator for Waste Management to estimate the reduced emissions that result.[21]

In Canada, prepackaged foods that will keep fresh for 90 days or less must be labeled with a ‘best-before’ date.[22] Many people wrongly assume this date indicates when an item becomes unsafe to eat — and should be immediately discarded — but most perishable foods remain edible after the date has passed. Canadahas established “National Food Waste Reduction Strategy” to respond to food waste.[23]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, public awareness campaigns have encouraged shoppers to make more frequent shopping trips so that people buy less food at a time and are more likely to make sure that food is used before expiration. UK has established “Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP)” which delivers consumer campaigns, and voluntary industry commitments under their Courtauld Commitment 2025.[24]

In Britain, the implementation of smaller portions and re-sealable packages have cut food waste by 21% since 2007.[25] They concluded based on best available data, food waste in the retail sector is small in comparison to other parts of the supply chain. According to WRAP, retail wastes around 0.2 million tonnes of food per year compared to 1.7 million tonnes in manufacturing and 7.3 million tonnes in the home.[26]

UK is introduced some preventive measures in waste reduction. In general, they follow these steps in food waste reduction.

1. Prevention: waste of ingredients, raw materials and food products arising is reduced-measured in overall reduction in waste

2. Redistribution to people

3. Use as animal feed

4. Recycling to compost or send for anaerobic digestion

5. Disposal send to landfill or discarded

UK has defined date labels with clear distinction between these three date labels as set out below:

“‘Use by’ dates refer to safety; “‘Best before’ dates refer to quality, display until dates are “used on-pack to assist retail staff with stock rotation.

European Union law has largely driven the policy and legal frameworks for waste management in the UK. however, the Brexit could cause disruption to some joint program of UK with European Union.[27]

France

In recent years, France has emerged at the forefront of the Food Waste Revolution, ranked number 1 by the Food Sustainability Index for their collective effort to reduce food waste. But the French are not yet done. France is determined to cut its total food waste in half by 2025. In France in 2014, a public awareness campaign entitled “Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables” used humor to encourage people to buy disfigured produce, which is equally as nutritious as their better-looking counterparts. Within the first two days of adopting this campaign, a single French supermarket sold 1.2 tons of disfigured produce. In 2016, France became the first country in the world to pass a law prohibiting large supermarkets from throwing away good quality food, approaching the “best before” date. In this principle any supermarket of more than 400 square meters in surface area must create a partnership with a food charity organization to donate its unsold food products instead of throwing them out.[28]

There are some other initiatives involved in reduction of food waste.

1. To encourage supermarkets/retailers to donate food products to charities.

2. To actively educate young people in combating waste using appropriate teaching materials.

3. To conduct an awareness-raising campaign via social media.

4. To Mobilize all stockholders in the food supply chain around a national anti-waste pact.

5. To have better and more clear definition and consumer education for best before date and use by date marking.

6. To encourage food businesses to do compositing and anaerobic digestion.

In France, Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Forestry in Action public policy is responsible for combating food waste. It should be noted that legislation banning supermarkets from disposing unsold food to landfill.[29]

USA

In the United States, food waste is estimated at between 30-40 percent of the food supply. This estimation is based on assessments from USDA’s Economic Research Service. This assessment shows 31 percent food loss at the retail and consumer levels, corresponded to approximately 133 billion pounds and $161 billion worth of food in 2010.[30] USDA and EPA created the food recovery hierarchy to show the most effective ways to address food waste.[31]

Moreover, US initiated some additional programs as follows.

1. U.S. Food Loss and Waste 2030 Champions is Launched by USDA and EPA in 2016, is for businesses and organizations that have made a public commitment to reduce food loss and waste in their own operations in the United States by 50 percent by the year 2030.

2. USDA and EPA created the food recovery hierarchy to show the most effective ways to address food waste. The premise of this principle is to reduce food loss and waste is not to create it in the first place. It is stated that waste can be avoided by improve product development, storage, shopping/ordering, marketing, labeling, and cooking methods. However, if excess food is inevitable, recover it and donate to hunger-relief organizations so that they can feed people in need. In addition, inedible food can be recycled into other products such as animal feed, compost and bioenergy.[32]

In 2015, the USDA joined with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to set a objective to cut US food waste by 50 percent by the year 2030.[33]

Australia

In Australia, $20 billion is lost to the economy through food waste,[34] over 5.3 million tonnes of food that is intended for human consumption is wasted from households and the commercial and industrial sectors each year.[35]

Australia started a massive program in halving food waste in Australia by 2030. In Australia, there is already a significant amount of work in progress to target food waste that is making a difference locally, regionally and nationally. The strategy seeks to control these efforts and identifies four priority areas where improvements can be made and they are, policy support, business improvements, market development, and consumers’ behaviour change.[36]

It is known households plays a major role in food waste production. It is estimated that Households throw away 3.1 million tonnes of edible food. Based on the survey done by Australia government the major reason for food waste production by homes are as follows.

1. Confusion over ‘use-by’ and ‘best-before’ date labelling

2. Over-purchasing of food that is then thrown away

3. Limited knowledge of how to safely repurpose or store food leftovers

4. Limited access to food waste collection systems

There are a number of steps introduced by Australian governments including:

1. To partner with food rescue organizations to donate food that would otherwise be wasted

2. To set sector-wide targets to reduce waste to landfill

3. To develop web-based wholesale marketplaces for surplus food and ingredients

4. To investigate packaging options to help reduce food waste

5. To fund businesses that buy infrastructure to process food waste on-site

Australia implemented its own waste hierarchy to effectively reduce food waste and achieve halving of Australia’s food waste by 2030.[37]

Japan

Japan ranked number second by the Food Sustainability Index for their collective effort to reduce food waste.[38] Japan started program called “Raising Awareness” consumer behaviour emerged as the root cause and as a large contributor to these problems; direct disposal, excessive peelings and food leftovers account for half the amount of national food waste.[39] It is noted that food businesses serve to high expectations and the preference for “perfect, unspoiled and pretty” products by paying careful attention to quality all along the food supply chain. This type of behaviour which caused some products to be discarded just before the best before date. In addition, the scrutinizing eye of the consumer on best-before dates encourages retailers to pull products from the shelves prematurely (before their sell-by dates) for fear of consumer rejects to purchase. Moreover, the situation has been aggravated by short sell-by dates for numerous prepared foods (some no longer than just a few hours at convenience stores) and consumers growing preference for freshness. Increased awareness of the dynamics of the food supply chain, more conscious purchase and consumption patterns, and cultural shifts in the valuing of food and better understanding best before date would have a knock-on effect on corporations and ultimately reduce waste production. The Japan government has shown commitment to improving consumer awareness on these issues. The inclusion of the consumer view in waste reduction efforts should take place through proper education (e.g. good knowledge about food labelling and storage) and clear and open communication between consumers and other stakeholders in order to ensure mutuality in the campaign to fight waste and food loss.[40] It should be noted that Japan is practicing all sort of food waste reduction in food waste reduction hierarchy including compositing and anerobic digestion.[41]

It is obvious there is one repeating solution proposed among developed countries and that is a clearer definition and consumer education for best before date and use by date marking. We need to understand the fundamentals behind this strategy proposed by almost all developed countries.

Dilemma with understanding of date markings

FAO estimates that 30 percent of the food supply is lost or wasted at the retail and consumer levels. One source of food waste arises from consumers or retailers throwing away large quantities of wholesome edible food because of confusion about the meaning of dates displayed on the label.[42] To reduce wasted food and consumer confusion , most of the food security international organizations including FAO, EC, USDA recommend that food manufacturers and retailers that apply product dating use a “Best if Used By” date.[43] ,[44] ,[45] Research shows that this phrase conveys to consumers that the product will be of best quality if used by the calendar date shown. Foods not exhibiting signs of spoilage should be wholesome and may be sold, purchased, donated and consumed beyond the labeled “Best if Used By” date.[46]

Types of Dates

1. A “Sell-By” date tells the store how long to display the product for sale. You should buy the product before the date expires.

2. A “Best if Used By (or Before)” date is recommended for best flavor or quality. It is not a purchase or safety date. “Best before” dates appear on a wide range of refrigerated, frozen, dried (pasta, rice), tinned and other foods (vegetable oil, chocolate, etc).

3. A “Use-By” date is the last date recommended for the use of the product while at peak quality. The date has been determined by the manufacturer of the product.

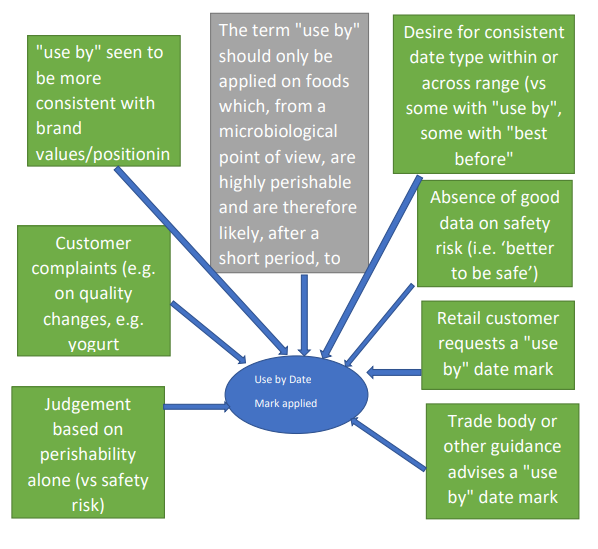

The term “use by” should only be applied on foods which, from a microbiological point of view, are highly perishable and are therefore likely, after a short period, to constitute an immediate danger to human health. “Use by” dates appear on highly perishable food, such as fresh fish, fresh minced meat, etc.

4. A “Freeze-By” date indicates when a product should be frozen to maintain peak quality. It is not a purchase or safety date

5. “Closed or coded dates” are packing numbers for use by the manufacturer.[47]

While there is clear distinction between type of dates, these several definitions of dates cause confusion for consumers. In fact, the research in EU shows that misconception by consumers of the meaning of these dates can contribute to household food waste. In addition, the way date marking is employed by food business operations and the regulatory authorities in managing the supply chain can also have a direct impact on food waste. Moreover, the approaches followed by food business operations in defining date marking whether to apply a “use by” or “best before” date, some industry practices (such as the amount of shelf life required by retailers on product delivery) and national guidelines on the further distribution and use of foods past the “best before” date can all impact the generation of food waste in the supply chain.[48]

There should be possible options tosimplify date marking on foodstuffs and promote better understanding and use of date marking by all stockholders.

First, one should understand that expiration dates do not always have to do with food safety; rather, they are usually manufacturers’ recommendations for highest quality. It is a fact if food products are stored properly, most foods (even perishable foods such as meat ) stay fresh several days past the “use-by” date. The rule of thumb is if a food looks, smells, and tastes okay, it should be fine for consumption. However, if any of these basics are off, then it is time to dispose the food.[49]

Second, the best-before date specifies to consumers that if the food product has been properly stored under conditions suitable to that product, the unopened product should have the peak quality until the specified date. This date does not guarantee product safety. Though, they it provides the consumer with information about the freshness and potential shelf-life of the unopened foods. It is important to note that a best-before date is not the same as an expiration date.[50]

Better understanding and use of date marking on food, i.e. “use by” and “best before” dates, by all food business operations and household consumers, can prevent and reduce food waste significantly.[51] The very straight forward understanding of date labelling is the distinction between “use by”- as an indicator of food safety -and “best before”- as an indicator of peak quality.

Third, “use by” dates are used only where there is a safety-based rationale, consistent with the country’s regulation. The term “use by” should only be employed on foods which, from a microbiological point of view, are highly perishable and are therefore likely, after a short period, to constitute an immediate danger to human health.

A study carried out by the European Commission, published in February 2018, estimates that up to 10% of the 88 million tonnes of food waste generated annually in the EU are linked to date marking.[52]

It is critical to note that any changes to food dating rules are proposed should meet these critical elements:

1. meet consumer information requirements,

2. can lead to food waste reduction,

3.it should not put consumer safety at risk.

The diagram below clearly demonstrates how to differentiate these two date markings and where and how they should be used by manufacturers or retailers.

Date marking practices: factors favouring “use by” vs “best before”

Figure 2: Date marking practices; source: ICF, 2018, courtesy to Date Marking Overview, EU action to promote better understanding and use of date marking

While it is important to reduce avoidable food waste linked to date marking It is critical that the product life is consistent with the findings of safety and quality tests, and is not reduced unnecessarily by other considerations, such as product marketing.[53]

Best Before – Good After

Nordic Council of Ministers developed following infographic explaining the date markings -Best before – Good After? Infographic, 2017.[54] The simplified diagram can be easily utilized by consumers.

Figure 3:Best before – Good After?

Some practical non-regulatory solutions for avoidable food waste

There are numerous studies have done in European Communities to reduce food waste.[55] Some of these methods are also used in developed countries.

1. It is found that is practical and completely safe to use dynamic durability in different season for some food products For instance it is possible to use longer shelf life during winter for dairy products.

2. The food manufacturers have to do testing for integrity, durability and safety of food after package opening – “Use by” should only be used on highly perishable food.

3. The regulators have to prepare guidelines for industry and consumers to clearly explain the difference between “Best before” and “Use by”.[56]

4. It was tested that packaging gas (60 % CO2/40% N2) gives longer shelf – from 10 to18 days for minced meat – 50 % less food waste in retail.[57]

5. Harmonization for lower storage temperature increase shelf life of some perishable products.

6. Shelf life for eggs should be regulated like any other food where producer is responsible for date marking.

7. The shift from «Use by» to «Best before» on fresh products reduce food waste without jeopardizing food safety.

• All dairy products

• Some meat products;

• Bacon

• Whole pieces

• Cured meats

• Liver paste

8. Use of different technology to increase shelf life:

a) MAP (modified atmosphere packaging)[58]: it creates longer shelf life for A wide variety of products: Fresh meat / Processed meat / Cheese / Milk powder/ Fresh pasta / Fruit & Vegetables / Ready Meals /Case ready meat / Fresh poultry / Fish & Seafood[59]

b) Change in packaging gas (C02/N2)[60]

This method causes 50 % less food waste specific for minced meat[61]

c) CO2 emitters: It will extend the shelf life of some fish by 50%

This method can increase Increased shelf life with 4 days for raw salmon filet[62]

9) Ensure more consistent date marking practices by food business operators and control authorities through scientific and technical guidance to be developed at country level

10) there is a level of consistency in storage of food at retail and guidance for consumers regarding the temperatures for storage at home.[63]

Possible regulatory actions to simplify and clarify date marking rules

It is possible to apply some regulatory measures in order to clarify date marking rules.

1. Modify the terminology tailored to the languages and level of consumer

understanding in each country.

a) It was found based on consumer research done at European Community that it is better to modify use by” to “use by end of” in order to clarify that the food is safe to eat until the end of the day indicated on the label.[64]

b) policy developments by CODEX Alimentarius, for instance it was proposed to modify “best before date” to “best quality before date”).[65]

c) To use mandatory graphical/visual presentation to highlight the different meaning of “Best before date” and “use by“.

d) To apply different symbol such as a STOP sign for “use by” or use colour coding – for instance using red colour for “use by” and green for “best before etc.

e) To define (with the aid of industry) the criteria on the basis for which the date mark is not required.

Conclusion:

Based on this study’s findings, my conclusion is that we can substantially reduce food loss and food waste from the supply chain by proper education and clear understanding of the causes of the food waste and loss. It is necessary to learn and share challenges, failures and success of each country is confronting food loss and waste. It is clear that date marking plays a critical role in food waste generation. This research shows that avoidable food waste linked to date marking is possible to be reduced where: a date mark is present, its meaning is clear in other words, consumers have a clear understanding of the meaning of date marking (and the difference between “use by” as an indicator of safety and “best before” as an indicator of quality); the product life and storage stated on the packaging is consistent with the findings of safety and quality tests. In addition, the available research demonstrates that additional date marking contributes to positive change in consumer behavior. It was shown that new technology in packaging is highly effective in extending shelf life. There are many other ways to reduce food loss and waste which are not included in this paper; therefore, further research is highly recommended.

Bibliography

Blue Environment (2016) Australian National Waste Report 2016. Prepared for the Department of the Environment and Energy. http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/d075c9bc-45b3-4ac0-a8f2-6494c7d1fa0d/files/national-waste-report-2016.pdf

British Retail Consortium (FOW0019)

Date Labelling on Pre-packaged Foods, Canadian Food Inspection Agency

Date Marking Overview, EU action to promote better understanding and use of date marking

DRAFT REVISION TO THE GENERAL STANDARD FOR THE LABELLING OF PREPACKAGED FOODS (CODEX STAN 1-1985)

Federal Green Challenge Web Academy September 24, 2015 , https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-09/documents/fgc-food-recovery-webinar-2015-09-24.pdf

Federica Marra, Fighting Food Loss and Food Waste in Japan, M. A. in Japanese Studies – Asian Studies 2011 – 2013 Leiden University, http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/save-food/PDF/FFLFW_in_Japan.pdf

Food and Agriculture Organisation (2017) Save Food: Global initiative on food loss and waste reduction. http://www.fao.org/save-food/en/. Accessed 19 September 2017; PMSEIC (2010) Australia and Food Security in a Changing World. The Prime Minister’s Science, Engineering and Innovation Council. http://www.chiefscientist.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/FoodSecurity_web.pdf. Accessed 18 September 2017

Food Loss and Food Waste http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en/

Food Sustainability Index 2017, http://foodsustainability.eiu.com/wp content/uploads/sites/34/2016/09/FoodSustainabilityIndex2017GlobalExecutiveSummary.pdf

Food Waste Composting: Institutional and Industrial Application Bulletin 1189 University of Georgia

FOOD WASTE DIGESTION Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste for a Circular Economy IEA Bioenergy: Task 37: 2018

Food waste FAQ, USDA https://www.usda.gov/foodwaste/faqs

Food waste in England Eighth Report of Session 2016–17, House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmenvfru/429/429.pdf

Global food losses and food waste, extend, causes, prevention FAO study http://www.fao.org/3/mb060e/mb060e03.pdf

Global food losses and food waste, FAO http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf

Guidelines to Minimize Wasted Food and Facilitate Food Donations NATIONAL ZERO WASTE COUNCIL

Haghirian, Parissa, ed. 2010. Japanese Consumer Dynamics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Highlights from date marking activities in Norway

http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A950731&dswid=-3469

http://www.foodbanking.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/GFN-The-State-of-Global-Food-Banking-2018.pdf

http://www.usda.gov/oce/foodwaste/sources.htm

https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste/eu_actions/date_marking_en

https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_eu-platform_20180420_sub-dm_pres-01.pdf

https://www.modifiedatmospherepackaging.com

Jancer, Matt, and Katie Peek. “How the World Wastes Food.” Popular Science 285.3 (2014): 34-35. Readers’ Guide Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson). Web. 15 Dec. 2014. Countries

Market study on date marking and other information provided on food labels and food waste prevention Executive Summary https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_lib_srp_date-marking_sum.pdf

Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Forestry (2016) The Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Forestry in Action. http://agriculture.gouv.fr/sites/minagri/files/plaqmingb72_0.pdf. Accessed 23 September 2017

Modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) is a way of extending the shelf life of fresh food products. The technology substitutes the atmospheric air inside a package with a protective gas mix. The gas in the package helps ensure that the product will stay fresh for as long as possible.

National Food Waste Strategy, Halving Australia’s waste by 2030- https://www.environment.gov.au/protection/waste-resource-recovery/publications/national-food-waste-strategy

National Zero Waste Council (2017) National Food Waste Reduction Strategy. National Zero Waste Council. http://www.nzwc.ca/focus/food/national-food-waste-strategy/Documents/NFWRS-Strategy.pdf. Accessed 13 September 2017

Parry, A., LeRoux, S., Quested, T. and Parfitt, J. (2015). UK food waste – historical changes and how amounts might be influenced in the future. Waste and Resources Action Programme, London.

ReFED (2016) A roadmap to reduce U.S. food waste by 20 percent. ReFED. www.refed.com. Accessed 13 September 2017.

Report «Food waste and date labelling»: THE STATE OF GLOBAL FOOD BANKING 2018: NOURISHING THE WORLD http://norden.divaportal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A950731&dswid=-3469

SARDI (2015) Primary Production Food Losses: Turning losses into profit. South Australian Research and Development Institute, Primary Industries and Regions South Australia.

Technical Platform on the Measurement and Reduction of Food Loss and Waste FAO guidance on food waste reduction- http://www.fao.org/platform-food-loss-waste/food-waste/food-waste-reduction/country-level-guidance/en/

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Summary of Compost Markets. Contact: 703-487-4650.

United Nations General Assembly (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Seventieth session, Agenda items 15 and 116. Resolution 70/1. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E. Accessed 16 September 2017.

USDA product labelling https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/regulatory-compliance/labeling/Labeling-Policies

[1] Food Loss and Food Waste http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en/

[2] Global food losses and food waste, FAO http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf

[3] Food Loss and Food Waste http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en/

[4] Food Loss and Food Waste http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en/

[5] Global food losses and food waste, FAO http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf

[6] Global food losses and food waste, extend, causes, prevention FAO study http://www.fao.org/3/mb060e/mb060e03.pdf

[7] Food and Agriculture Organisation (2017) Save Food: Global initiative on food loss and waste reduction. http://www.fao.org/save-food/en/. Accessed 19 September 2017; PMSEIC (2010) Australia and Food Security in a Changing World. The Prime Minister’s Science, Engineering and Innovation Council. http://www.chiefscientist.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/FoodSecurity_web.pdf. Accessed 18 September 2017

[8] Jancer, Matt, and Katie Peek. “How the World Wastes Food.” Popular Science 285.3 (2014): 34-35. Readers’ Guide Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson). Web. 15 Dec. 2014. Countries

[9] Food Waste Composting: Institutional and Industrial Application Bulletin 1189 University of Georgia

[10] Federal Green Challenge Web Academy September 24, 2015

[11] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Summary of Compost Markets. Contact: 703-487-4650.

[12] Federal Green Challenge Web Academy September 24, 2015

[13] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Summary of Compost Markets. Contact: 703-487-4650.

[14] Food Waste Composting: Institutional and Industrial Application Bulletin 1189 University of Georgia

[15] FOOD WASTE DIGESTION Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste for a Circular Economy IEA Bioenergy: Task 37: 2018 : 1

[16] THE STATE OF GLOBAL FOOD BANKING 2018: NOURISHING THE WORLD

http://www.foodbanking.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/GFN-The-State-of-Global-Food-Banking-2018.pdf

[17] United Nations General Assembly (2015) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Seventieth session, Agenda items 15 and 116. Resolution 70/1. http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E. Accessed 16 September 2017.

[18] Technical Platform on the Measurement and Reduction of Food Loss and Waste FAO guidance on food waste reduction- http://www.fao.org/platform-food-loss-waste/food-waste/food-waste-reduction/country-level-guidance/en/

[19] Technical Platform on the Measurement and Reduction of Food Loss and Waste FAO guidance on food waste reduction- http://www.fao.org/platform-food-loss-waste/food-waste/food-waste-reduction/country-level-guidance/en/

[20] Food and Agriculture Organisation (2017) Save Food: Global initiative on food loss and waste reduction. http://www.fao.org/save-food/en/. Accessed 19 September 2017; PMSEIC (2010) Australia and Food Security in a Changing World. The Prime Minister’s Science, Engineering and Innovation Council.

[21] Guidelines to Minimize Wasted Food and Facilitate Food Donations NATIONAL ZERO WASTE COUNCIL

[22] Date Labelling on Pre-packaged Foods, Canadian Food Inspection Agency

[23] National Zero Waste Council (2017) National Food Waste Reduction Strategy. National Zero Waste Council. http://www.nzwc.ca/focus/food/national-food-waste-strategy/Documents/NFWRS-Strategy.pdf. Accessed 13 September 2017

[24]7. Parry, A., LeRoux, S., Quested, T. and Parfitt, J. (2015). UK food waste – historical changes and how amounts might be influenced in the future. Waste and Resources Action Programme, London.

[25] Food waste in England Eighth Report of Session 2016–17, House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmenvfru/429/429.pdf

[26] British Retail Consortium (FOW0019)

[27] Food waste in England Eighth Report of Session 2016–17, House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmenvfru/429/429.pdf

[28] Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Forestry (2016) The Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Forestry in Action. http://agriculture.gouv.fr/sites/minagri/files/plaqmingb72_0.pdf. Accessed 23 September 2017

[29] Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Forestry (2016) The Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Forestry in Action. http://agriculture.gouv.fr/sites/minagri/files/plaqmingb72_0.pdf. Accessed 23 September 2017.

[30] Food waste FAQ, USDA https://www.usda.gov/foodwaste/faqs

[31] Federal Green Challenge Web Academy September 24, 2015

[32] ReFED (2016) A roadmap to reduce U.S. food waste by 20 percent. ReFED. www.refed.com. Accessed 13 September 2017.

[33] Food waste FAQ, USDA https://www.usda.gov/foodwaste/faqs

[34] SARDI (2015) Primary Production Food Losses: Turning losses into profit. South Australian Research and Development Institute, Primary Industries and Regions South Australia.

[35] Blue Environment (2016) Australian National Waste Report 2016. Prepared for the Department of the Environment and Energy. http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/d075c9bc-45b3-4ac0-a8f2-6494c7d1fa0d/files/national-waste-report-2016.pdf

[36] National Food Waste Strategy, Halving Australia’s waste by 2030

[37] National Food Waste Strategy, Halving Australia’s waste by 2030

[38] Food Sustainability Index 2017, http://foodsustainability.eiu.com/wp content/uploads/sites/34/2016/09/FoodSustainabilityIndex2017GlobalExecutiveSummary.pdf

[39] Federica Marra, Fighting Food Loss and Food Waste in Japan, M. A. in Japanese Studies – Asian Studies 2011 – 2013 Leiden University, http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/save-food/PDF/FFLFW_in_Japan.pdf

[40] Haghirian, Parissa, ed. 2010. Japanese Consumer Dynamics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

[41] Federica Marra, Fighting Food Loss and Food Waste in Japan, M. A. in Japanese Studies – Asian Studies 2011 – 2013 Leiden University, http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/save-food/PDF/FFLFW_in_Japan.pdf

[42] http://www.usda.gov/oce/foodwaste/sources.htm

[43] http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en/

[44] USDA product labelling

[45] https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste/eu_actions/date_marking_en

[46] http://www.usda.gov/oce/foodwaste/sources.htm

[47] USDA product labelling

[48] https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste/eu_actions/date_marking_en

[49] Date Marking Overview, EU action to promote better understanding and use of date marking

https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_eu-platform_20180420_sub-dm_pres-01.pdf

[50] Date Labelling on Pre-packaged Foods, Canadian Food Inspection Agency

[51] Market study on date marking and other information provided on food labels and food waste prevention Executive Summary https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_lib_srp_date-marking_sum.pdf

[52] Date Marking Overview, EU action to promote better understanding and use of date marking

https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_eu-platform_20180420_sub-dm_pres-01.pdf

[53] Date Marking Overview, EU action to promote better understanding and use of date marking

https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_eu-platform_20180420_sub-dm_pres-01.pdf

[54] Highlights from date marking activities in Norway

[55] Market study on date marking and other information provided on food labels and food waste prevention Executive Summary https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_lib_srp_date-marking_sum.pdf

[56] Date Marking Overview, EU action to promote better understanding and use of date marking

https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_eu-platform_20180420_sub-dm_pres-01.pdf

[57] Highlights from date marking activities in Norway

[58] Modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) is a way of extending the shelf life of fresh food products. The technology substitutes the atmospheric air inside a package with a protective gas mix. The gas in the package helps ensure that the product will stay fresh for as long as possible.

[59] https://www.modifiedatmospherepackaging.com

[60] Gas flush consists of an inert gas such as nitrogen, carbon dioxide, or exotic gases such as argon or helium which is injected and frequently removed multiple times to eliminate oxygen from the package

[61] Report «Food waste and date labelling»: THE STATE OF GLOBAL FOOD BANKING 2018: NOURISHING THE WORLD http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A950731&dswid=-3469

[62] https://nofima.no/en/nyhet/2016/03/better-salmon-fillet-with-carbon-dioxide-co2/

[63] Date Marking Overview, EU action to promote better understanding and use of date marking

https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_eu-platform_20180420_sub-dm_pres-01.pdf

[64] Date Marking Overview, EU action to promote better understanding and use of date marking

https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/fw_eu-platform_20180420_sub-dm_pres-01.pdf

[65] DRAFT REVISION TO THE GENERAL STANDARD FOR THE LABELLING OF PREPACKAGED FOODS (CODEX STAN 1-1985)